French horn quartet plays live for a real-time MRI study

“Okay, are you ready? Let's go,” Peter Iltis speaks into the little microphone standing on the table in front of him. Shortly thereafter, the sounds of a brass instrument are broadcasted via the intercom. But the music does not come from a recording studio or a stage, but out of a large medical device – an MRI system located two rooms away.

The US American is a professor of kinesiology at Gordon College Wenham in Massachusetts (United States) and currently visiting the MPI for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, the only place where – as he puts it – he can find what he is looking for: a possible therapy and prevention for focal dystonia, an occupational disease that affects professional brass players: The musicians develop cramps of the tongue and lips so that they can no longer play their instrument at the highest level. So far, however, little is known about how lip and tongue movements of affected musicians differ from unaffected players. About two to three percent of all professional brass musicians suffer from focal dystonia, and this can mean the end of professional playing for them. Iltis is affected by the disease himself and had to give up his musical career.

Musicians in real-time MRI

Finding a way to combat focal dystonia

Now he is sitting in the control room of Jens Frahm, who heads the Biomedical NMR Group at the Göttingen institute. In the 1980s, Frahm developed FLASH, a method which massively accelerated MRI and paved the way for its broad clinical application. In 2010, Frahm's team achieved another breakthrough: FLASH 2 now makes it possible to generate images in real time, thus allowing to record videos live from inside the human body. He now provides Iltis with this technology, who, together with professional brass players, wants to create a database of real-time MRI films of horn, trumpet, and trombone players, the MRI Brass Repository. With the help of this unique data collection he wants to provide a rich source of information for clinicians and researchers world-wide to assist in finding a way to combat focal dystonia in brass players.

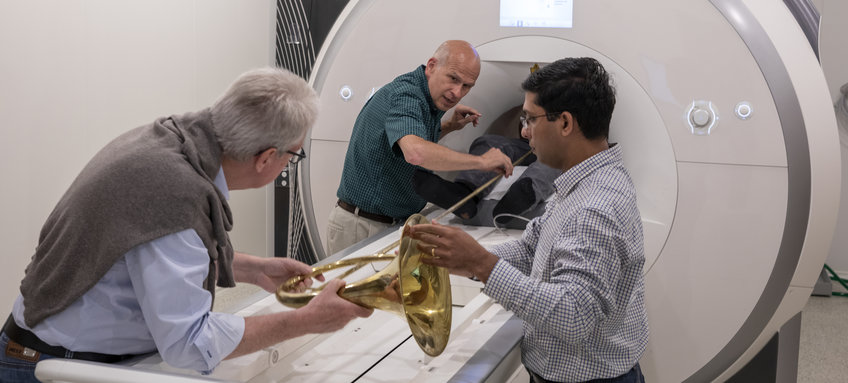

In the ‘tube’ from where the melody originates Iltis hears over the loudspeaker, Christoph Eß is lying. He is principal horn player of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, professor at the University of Music Lübeck, and part of the horn quartet german hornsound. Eß is not affected by focal dystonia. Today in the MRI system, he does not blow a conventional horn as this would not fit in there. Instead, he plays a custom-made instrument that protrudes from the magnet: It looks like a horn that was unrolled and had the valves removed. Using a mirror, the musician can look out of the magnet onto a screen showing the notes for the next exercise. A red spotlight next to the screen serves as a timing device to regulate the performance. After four signals from this optical metronome and the announcement of Iltis, the next measurement begins.

The musicians can observe themselves while playing

While Eß is playing, Iltis concentrates on how the hornist’s mouth and tongue are moving. The MRI system delivers real-time images at 25 frames per second simultaneously from two different perspectives, showing the longitudinal and cross-sectional view of Eß's mouth and throat. The tongue’s position is clearly visible with every tone and every playing technique. Most brass players do not know how their tongue moves while playing as there are relatively few position-sensing nerves there. However, with real-time MRI they can develop a more precise sense of how their tongue moves and how they play their instrument. The musicians can observe themselves while playing in the magnet, which gives direct feedback, and thus can develop a kind of eye-tongue coordination.

Eß is one of almost 100 subjects participating in the study in Göttingen – his quartet colleagues Sebastian Schorr, Stephan Schottstädt, and Timo Steininger from german hornsound are also present today. The professional musicians are standing behind Iltis and Frahm's team of researchers, following the real-time MRI video of Eß with rapt attention. Then it is their turn to play the same precisely defined exercises in the magnet.

Iltis' research shall not only benefit professional musicians and scientists researching focal dystonia. Already today, the real-time recordings of the MRI Brass Repository Project are widely used for pedagogic purposes by teachers, providing their students with a new approach to playing their instrument. Later, the database will be available to researchers and brass teachers via the internet through a vetted application process.

The last MRI recording of the day is not a simple exercise, but a short piece of music. Now everything has to fit perfectly, because Iltis has something special in store – not in the name of science, but for the arts: a compilation of MRI videos of these performers playing a famous horn trio from Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony – the first real-time MRI horn ensemble performance. Iltis is happy and activates the microphone once again: “Very good, thank you Christoph. That was really great!” (jp/fk)